Low-Speed Rail

Architect & urbanist Robert Orr, from New Haven, CT wrote a piece on his Facebook page this week that really caught my eye. Appended below, Robert makes an excellent case for why we it would make more sense to focus on an incremental approach to improving our rail network, rather than leaping into very expensive true high-speed rail (HSR).

The push to improve our rail network is often couched in an either-or mindset. Either we must have true HSR, like Europe and Japan, or we are must stick to funding highways and airports. In fact, there really is a third way forward, much like Robert mentions. We could make incremental improvements, with very modest expenditures, that would dramatically improve our passenger rail network in the entire country.

I’m not an opponent of true HSR by any means. In fact, I love it – it’s insane to me that for such a wealthy country that we don’t have in 2012 what many other countries have had for over 20 years now. I first rode the French TGV in 1993, and I absolutely do think people will use it when we do have it – people will realize its many benefits compared to driving long-distance or flying.

But in the meantime, that shouldn’t stop us from upgrading our existing rail system today, so that we have a true alternative that is at least 20th century technology. For example, the Midwest High-Speed Rail plan that has been in the works for well over a decade, was slated to cost 7.7 billion dollars in 2002, to upgrade the entire network to 110mph. That’s about 9.8 billion in 2012 dollars.

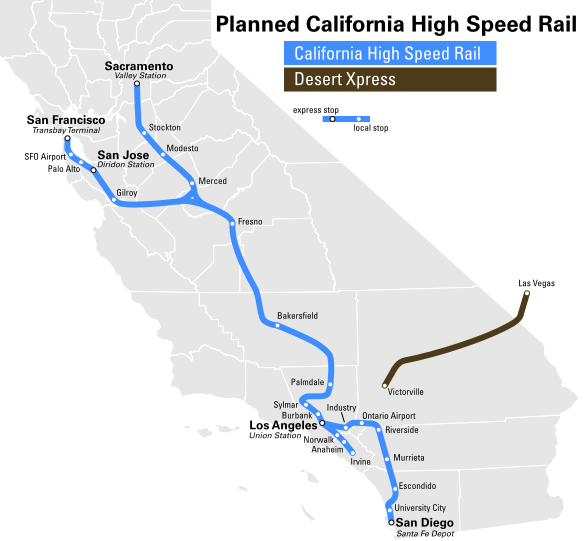

10 billion sounds like a lot of money, I know, especially in this politically-charged environment. But consider this by way of reference: the California HSR line, at 220 mph, is slated to cost 68 billion dollars. That’s for one trunk line, and a couple of extensions, in one (albeit very-populated) state: 6 times the cost of the entire Midwest HSR plan. Or, if you prefer, an airport comparison: in Kansas City, plans are well underway to build a new terminal at Kansas City International Airport. That terminal is estimated to cost 3 billion dollars. One airport terminal, in one city, will cost an amount almost 1/3 of the cost to build an entire regional rail system that provides real transportation alternatives and economic development to existing communities.

We like to think of rail as something that’s expensive – a luxury we cannot afford. Instead, we pour our money into less-efficient forms of transportation, with very dubious return on our investments. And, for all the talk about the failures of Amtrak, we overlook the fact that except for Southwest, airlines simply do not make money. It's time to get beyond the either-or, and recognize what can very easily be accomplished today and tomorrow, not just five years from now. And, importantly, we need to recognize the importance of networks. As we've seen with bike lanes, the better the network, the greater the amount of users.

I’m with Robert – 3 cheers for low-speed rail!

LOW SPEED RAIL!

by Robert Orr

I travel by rail frequently, mostly because flying has become so unappealing.

I have a GPS speedometer on my cell phone and note with surprise how often the train travels at speeds at or above 130 MPH. These are standard trains, not the Acela. I've tested the GPS speedometer in my car (not at 130 MPH!) where it registers pretty close to what the dashboard speedometer reads, so the 130 MPH reading is accurate.

Despite these speed capabilities, the trip from New York to Chicago takes 19 hours. The distance is 960 miles, meaning the average speed is 50 MPH. If the train could get closer to its capabilities (and I mean current capabilities with no enhancements) the Chicago schedule would be more like the time it takes between New Haven and Washington on the Regional, and the HVN/WAS trip could drop in half too.

As a traveler, I note the amount of time trains stop and sit. Time's built into schedules to account for track conflicts. A conductor once lamented, "You can't go any faster if something's in front of you."

Freight companies, mostly CSX, actually own the tracks and haul considerably more revenue, which gives them priority over passenger rail. So passengers like me sit and wait.

The principal sources for the congestion are antique laws left over from robber baron days that levy punitive tax on physical rails. Partly due to the tax, partly due to maintenance costs and partly due to lower passenger traffic, Amtrak made an ill-conceived decision to remove two of typically four tracks to "sweeten" the deal before selling their lines –– never mind the millions of taxpayer dollars it cost to remove the tracks and the Olympian misunderstanding of the need for four tracks. "It's not about capacity, it's about passing," the same conductor hastened to rant as he decried the deaf ear Washington stubbornly held against his Union's lobbying efforts years back.

On national news we hear constant wrangling regarding high speed rail, especially its limited service points and its zillion dollar price tag, which keep killing its prospects.

What to do? For a start, "low speed rail" is actually pretty fast, if only we could remove the barriers. It seems to me that artificial intelligence is well beyond the point where it could solve the scheduling problems brought on by the limited number of rails. With proactive scheduling and faster trips, the attractiveness of regular rail would skyrocket without spending (comparatively) any money at all.

The next step would be to remove the retarded tax barrier and add tracks back to further increase efficiency, speeds (with present equipment), and passenger usage. This too would be a fraction of the cost of high speed rail.

And lastly, recommission (and repair) abandoned track lines lying fallow under leaves or scuttled by "rails to trails" programs. Launch leaf raking and "trails to rails" programs and suddenly we have a functional connected system that serves even small towns, illustrated by the pre-decommisioning map below.

The first part (scheduling) seems like low hanging fruit for the coworking tech-savvy crowd. It's time to launch a hugely profitable venture with cheap resources well in hand.

If you got value from this post, please consider the following:

- Sign up for my email list

- Like The Messy City Facebook Page

- Follow me on Twitter

- Invite or refer me to come speak

- Check out my urban design services page

- Tell a friend or colleague about this site